400 millions years evolution deserve some respect

-* -430/-400 My, thorny sharks or the acanthodians with a cartilaginous skeleton and osseous jointives scales

- -400/-350 My, 3 classes of fish appeared :

- The armoured fish which died out in the Carboniferous period,

- The cartilaginous fish from which actual sharks have evolved,

- The osseous fish from which most of the modern fish species have evolved (a branch of which engendered the amphibians, from which will derive reptiles, mammals and birds).

- -350 My: the Cartilaginous fish types divided in 2 sub-classes: :

- The Elasmobranchs which are strictly speaking sharks, among whom are the selachians which will engender a new group: that of the skates,

- The Holocephales or chimaeroid fishes which adapt themselves to abyssal zones (some rare species remain such as elephant fish).

8 Orders of SharksInternet Source

8 Orders of SharksInternet Source

- -50 My: the first modern Tiger shark (genus Galeocerdo).

- The most terrible: the Carcharocles megalodon, 15 metres in length, with 15cm-teeth, as massive as the Whale shark but carnivorous.

- The giant Shortfin Mako shark (Isurus hastalis), the Great White’s ancestor.

- Many shark species adopted their modern shape 100 My ago and have hardly evolved since, what would be the sign of a completed adaptation to their environment.

Nota : Disappearance of dinosaurs: - 65 Million years (My).

Sharks’ classification

The 565 species of sharks known to date (2022) are classified into the following eight orders based on certain physiological parameters.

Elements of anatomy

The outline

The typical squale has a lengthened body; the trunk is cylindro-conical - in torpedo - with an almost flat lap face, a roun snout, a lap mouth, armed with several rows of teeth. But among the 549 species, there are a big variety of sizes and aspects.

The head, jaw and teeth

The skeleton of the head consists of 2 parts:

- The Neuroskull: a box of cartilage which protects the encephalon, including the seat of the olfaction which is highly developed, the seat of taste, balance and the endocrine system (pituitary gland), the seat of vision, memory and driving coordination

- The Splanchnocranium: this concerns the jaw and the brachial gill slits.

The jaw of the majority of the modern sharks is hyostylic: that means it is independent from the skull, what allows a spectacular extension of jaws to attack big prey and a prehension (pressure of the jaw) of significant power. For example, a 3-metre shark possesses a jaw pressure of 3 tons/cm ².

Teeth grow inside the gum, in successive rows and become functional when they coincide with the fish bone (edge) of the mouth. Eventually they wear out and fall off.

Their shape varies according to the type of predation. The Bull shark possesses disentangled teeth adapted to the capture of slippery fish; the Port-Jackson shark has almost flat teeth, used to crush shells.

The shark’s eyes

On lateral-back position, eyes have two eyelids. Often a nictitating membrane, called a “third eyelid" can be seen.

The snout

At the end of the snout, two symmetric but independent nostrils, which play no role in breathing. These nostrils constitute organs of olfaction.

The body

The shark’ skin is so rough it can be used as sandpaper. It consists of uncountable dermal denticles, which are small rough placoïd scales, homologous in structure to teeth. As a result, the skin is often dried and used as a leather product or sandpaper. It would seem that these denticles are aligned in several rows, channelling the water to produce a laminar flow and hence reducing resistance to movement in the water.

This skin structure allows the shark to be almost silent in the water, a certain advantage for a predator.

The gill slits

On each side and at the back of the head, are brachial gill slits, 5 pairs for most shark species, but 6 or 7 to hexanchiforms.

Gill openings are very fragile organs without a protective membrane; they are mobile and can be contracted or dilated. They can be damaged by pollution or blocked by parasites (there are frequent observations of fish specialised in cleaning gill openings).

The fins

Shark use their fins for stabilising, steering, lifting and propulsion. Each of the fins is used in a different manner.

There are one or two fins present along the dorsal midline called the first and second dorsal fins. These are “anti-roll/stabiliser” fins. These two fins may, or may not have, spines at their insertion. When spines are present they are defensive, and may also have skin glands associated with them that produce an irritating substance.

Pectoral fins originate behind the head and extend outwards. These fins are used for steering during swimming and help to provide the shark with lift.

Pelvic fins are found near the cloaca and are also stabilisers. In males they have a secondary function as they are modified into copulatory organs called claspers.

Anal fins may be absent, but if present, they are located between the pelvic and caudal fins.

The tail region itself consists of the caudal peduncle and the caudal fin. The caudal peduncle may have notches known as precaudal pits found just ahead of the caudal fin. The caudal fin has both an upper and lower lobe that can be each of different sizes and their shape varies according to the species.

Two dorsal fins, of variable forms and sizes, depending on the species, are situated on the sharks’ back:

The first dorsal fin can be raised in aileron or, on the contrary, lowered.

The second dorsal fin is smaller and fatter. Even here, hexanchiformes distinguish themselves by their unique dorsal fin.

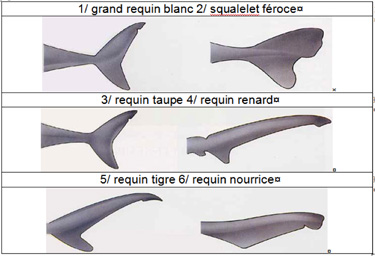

The caudal fin of the Tiger shark and of the Blacktip shark

The tail includes 2 uneven, sometimes almost symmetric lobes (i.e. great white shark) and it determines the type of propulsion of the animal.

A hetereocercal tail: the upper lobe is longer and heavier than the lower lobe (blacktip shark, tiger shark).

This species moves by rocking its body from one side to the other, the upper lobe delivering the maximum of the necessary power to swim slowly or accelerate rapidly.

The types of prey of these sharks require them to be able to bend and to turn quickly.

The caudal fin of the Shortfin Mako and of the Great White

The tail of the great white shark is different: it provides the propulsion for a more heavily built body.

This shark, which is closer to the Common Shark-mole and to the shortfin Mako, travels more by the movement of its tail than by the balance of the body.

The important lower lobe assists with high speed and the side hulls, on the base of the tail, reduce the trail hydrodynamics. The shape of the porbeagle caudal fin, like the one in this picture is lunate or crescent shaped. This means that the upper and lower lobes of the tail fin are similar in size.

The caudal fin of the Nurse shark

The Nurse shark spends most of its time on the sea floor (caves, crevices). It does not travel over great distances. As Invertebrates establish the main part of its diet, it does not need a tail assuring a high speed, but it needs considerable flexibility.

The lower lobe of its tail is almost confused with the upper lobe; so, its tail makes wide sculling movements, it swims in a similar fashion to an eel.

The caudal fin of the Tresher shark

The 3 species of Tresher sharks, that live in the tropical and moderate oceans, are powerful swimmers.

Active hunters of fish and squid, they use an original hunting technique: they gather their prey before knocking them out thanks to the very elongated caudal lobe.

The extension of the tail, almost as big as the rest of the body, does not affect the speed and efficiency of these hunters.

Elements of physiology

Breathing

The sharks’ breathing mode depends on the lifestyle of the particular species:

Pelagic species swim continuously; if they stop, they will be asphyxiated ; benthic sharks spend their day on the sea bottom. Brachial breathing is convenient for the benthic and sedentary species. They inhale water and pass it through their gill slits without needing to swim or to be in a moving current. They dilate their pharynx and open their mouth. The principle used is to pump water by muscular contractions.

To move, the ‘open sea’ sharks need a major contribution of oxygen. If they stop swimming, it is suffocation. Water enters through the mouth and is filtered out through the gill slits. It is same principle as a “ramjet engine”: these sharks (Carcharhinadae and Lamnidae) use this flow of water which is filtered by gill slits, opening onto 5 to 7 gill slits, to extract the oxygen from it.

Certain sharks (such as bull sharks) can alternate their breathing either by swimming, or sucking up the water according to their current situation. Others can benefit by eating and by breathing at the same time (whale shark). Certain nurse sharks can intake water by their anterior gill openings and expel by their posterior gill openings, assuring a complete dissociation of the feeding and respiratory functions.

The efficiency of breathing also depends on the quantity of haemoglobin in the blood. This rate varies according to the species from 3g to 14g for 100ml of blood.

The copulatory organs

To mate, the pelvic fin is enlarged, on its internal edge, by a stiff, fluted stalk, which is called clasper and which constitutes the copulation organ. Provided with 2 claspers, the shark can use only one at a time. A siphonale gland sends the sperm from the cesspool to the clasper, which is not directly bound with testicles.

The buoyancy

To decrease their physical density and facilitate active swimming, elasmobranchs developed (as they don’t have a swim bladder), an organ allowing a neutral buoyancy: the liver.

In certain species, the hepatic gland can reach 25 % of the total weight of the body (blue skin shark).

The liver is also an enormous reserve of energy. The major hydrocarbon in this oil is called squalene. The oil of the liver of both rays and sharks is rich in vitamin A.

Squalene, coming from shark’s liver oil, is used in particular in food supplements to, it seems, strengthen the immune system. These supplements are sold in certain “organic” stores and on the Internet. It is also used in beauty care, in moisturising creams as an agent that quickly penetrates the skin. Squalene is also used as an additive: one of the substances, administered together with a vaccine, which stimulate the immune system and increase the response to the vaccine.